In memoriam: Alasdair MacIntyre

In memoriam: Alasdair MacIntyre

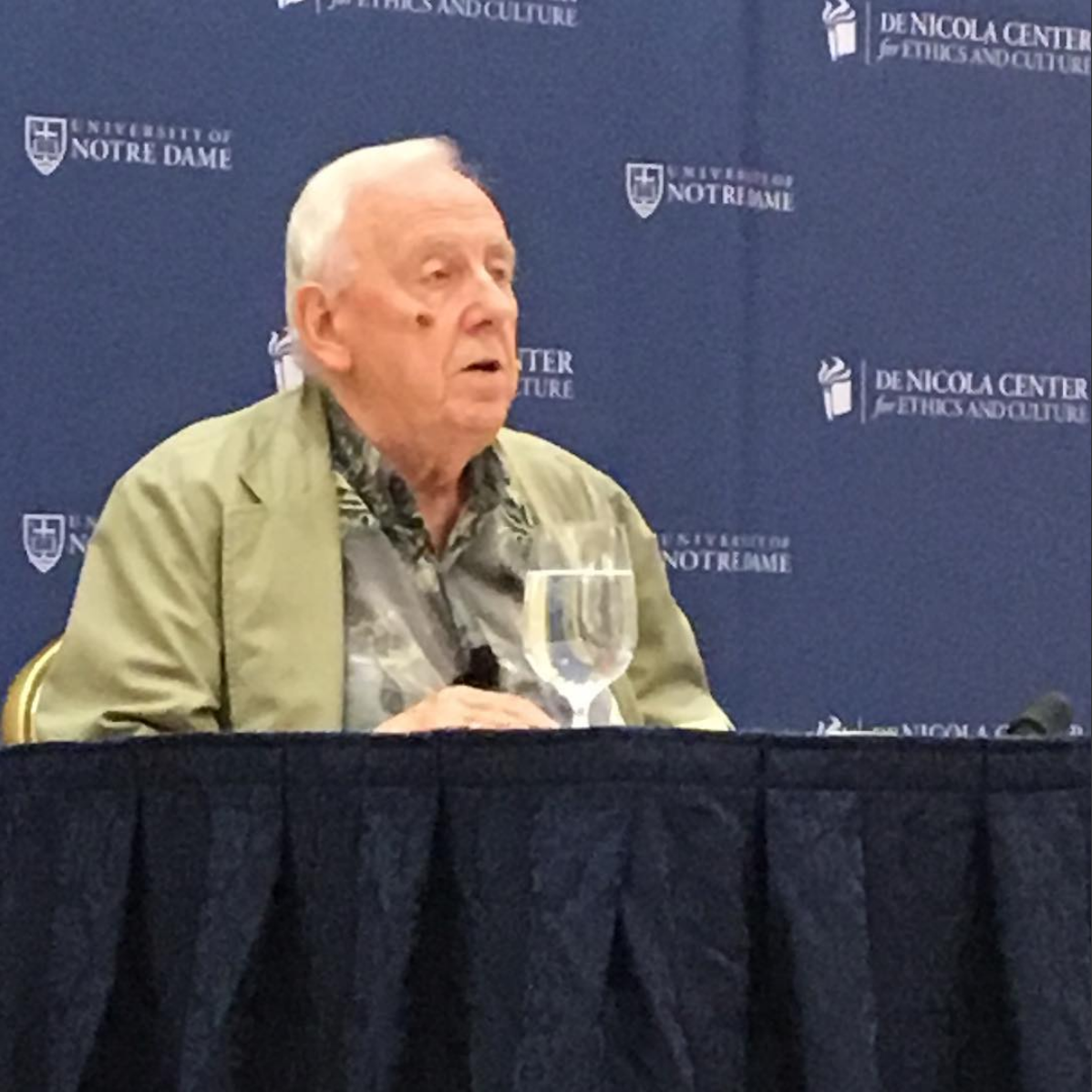

Alasdair MacIntyre is dead. He had a very good run, better than many could dream of: he was 95 years old, and produced an output significant enough to be in competition for the title of “greatest philosopher of his age”. Few indeed are the 20th- or 21st-century philosophers who have an entire learned society – in his case the International Society for MacIntyrean Enquiry (ISME) – devoted to pursuing the implications of their work. It seems that MacIntyre himself was a little uncomfortable with that society’s existence. The one time I ever saw MacIntyre in the flesh was at the society’s 2019 conference, held on the University of Notre Dame campus near his home, in honour of his 90th birthday – but, I was told, he only participated on condition that his name not appear anywhere in the conference title. (Thus, given his focus on teleology and the aims of human life, the conference was called “To What End?”)

Even now, MacIntyre still sits outside what is usually considered the philosophical mainstream. Though he was trained in the English-language mainstream of analytic philosophy and taught in analytic departments, he refused to confine himself to the analytic mode of philosophizing, always writing in a way broader and less precise than analytic departments were usually willing to count as good philosophy. That experience surely shaped one of MacIntyre’s more powerful philosophical insights: the recognition that philosophy itself always operates within the context of historical tradition – the conception of tradition at issue being close to Thomas Kuhn’s concept of paradigms. Kuhn and MacIntyre recognized that different paradigms differed not just on what claims they believed to be true and false, but on the standards by which one judged them true and false; MacIntyre knew that within philosophy, analytic philosophy’s standards were never the only ones available.

Thus MacIntyre is the sort of philosopher whom one often first encounters in unusual ways, outside being taught him in a classroom. Thus one colleague at “To What End?” helpfully started conversations with “What’s your MacIntyre story?” – imagining, rightly, that everyone had their own personal story of encountering his ideas, more interesting than being simply taught him in an Intro to Ethics class. (Now that I think of it, the one place I remember being asked a similar question was on a long tour around the Laphroaig whisky distillery in Scotland, which also began with the guide asking “What’s your Laphroaig story?” – a comparison that would likely have pleased MacIntyre, as he always took his philosophy to be deeply informed by his Scottishness.)

Most people’s MacIntyre story revolves around his first major work, After Virtue, and mine is no exception. My undergraduate inquiries in analytical ethics had left me unsatisfied, entering long debates about what was “moral” or made something “moral”, without any discussion of why one should be “moral” in the first place. In that environment, After Virtue changed my life: it took Nietzsche’s critiques of “morality” seriously, arguing Nietzsche was generally right that contemporary English-language defences of “morality” were built on a house of cards. After a long frustration with analytical ethicists’ reliance on “intuition”, new worlds opened up to me in MacIntyre’s acerbic comment that “one of the things that we ought to have learned from the history of moral philosophy is that the introduction of the word ‘intuition’ by a moral philosopher is always a signal that something has gone badly wrong with an argument.” (69)

To that extent of the Nietzschean critique, MacIntyre’s philosophy aligned with the postmodernist views then ascendant in “continental” philosophy. But part of the genius of After Virtue was that it refused to follow the postmodernists all the way to their anything-goes relativism, where all claims about goodness were just masks for power relations. The problem, MacIntyre argued, lay specifically in the analytical way of doing things, and especially in its refusal to admit the nature of its assumptions, historically grounded within traditions of inquiry.

After Virtue was in many respects an intentionally destructive work, as Nietzsche’s is: clearing away problematic assumptions and approaches in order that a better approach might be built. The project of MacIntyre’s later work, quite appropriately (and unlike Nietzsche’s), was to build up a conception of what that more traditionally grounded philosophy would look like, in both methodological and substantive terms: both defending the approach of an inquiry grounded inquiry in tradition (as he did in Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry) and building up one such specific traditionally grounded approach in practice.

But which tradition? In After Virtue MacIntyre had suggested the choice that faced us was “Nietzsche or Aristotle?”, and indicated the latter was the preferable option. He never lost his allegiance to Aristotle – but he did take a surprising twist in his next book, Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, where the specific flavour of Aristotelian tradition he embraced was Thomas Aquinas’s Catholic natural-law theory. That move lost him a number of fans – most notably his fellow Aristotelian Martha Nussbaum, whose review of Whose Justice? expressed a bitter disappointment at the loss of what she had previously considered an ally.

That substantive Thomist Catholic commitment would shape the rest of MacIntyre’s thought and life. He moved professionally to Notre Dame, a university committed to its Catholicism, and lived nearby for the rest of his life. MacIntyre won some of his biggest fans – especially in Latin America – among conservative Catholics, who found in his thought a lifeline for defending their views, in the context of an academia usually hostile to them.

But his politics could not be so easily pigeonholed. Before After Virtue he had begun his career with sympathies to Marxism as well as Christianity, exploring connections between them the early work called Marxism: An Interpretation or Marxism and Christianity. (Many readers have found this work unimpressive, but it leaves more of an impression if one knows he wrote it at age twenty-three.) Late in life, importantly, he returned to Marx without leaving Thomism, noting in the epilogue to his festschrift that “Thomists have some important lessons to learn from Marxists” (482) on the historical and social circumstances that shape human practical reasoners. He built up those connections at greater length in his final book, Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity.

Thus MacIntyre leaves the legacy of an ISME split between Thomist right-MacIntyreans and Marxist left-MacIntyreans – yet one where, by all accounts I’ve heard, the debates between right and left are conducted with mutual respect. That, of course, is all too much of a rarity in our present era. It is a testament to the power of MacIntyre’s thought that it can spark the creation of such a community: people from otherwise opposed camps coming together for a shared intellectual project. And that seems like a legacy MacIntyre would appreciate, since in Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, coming together for shared projects was itself one of the more prominent themes.

- News

- Mysticism

- Horoscope

- Bath & Body

- Soap Making

- Books

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film

- Fitness

- Food

- الألعاب

- Gardening

- Health

- الرئيسية

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- أخرى

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness